<

Much of the evolution in western art music can be looked at in terms of gradual acceptance of increasing dissonance in the pitch domain. Much of Nancarrow's work explores temporal dissonance, that is, in which two or more simultaneous different tempi interfere with each other, much as the overtones of simultaneous pitches do to various degrees.

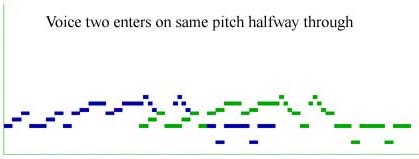

In traditional canons, each voice enters at the same tempo as the original and its notes combine with those of the first to imply the desired harmony. In the example below (the tune "Frere Jacques"), the second voice enters after two measures. The original voice is written in such a way that it combines to make tonic and dominant harmonies when it is layered upon itself. The diagrams that follow represent time along the x-axis and pitch along the y-axis, like a player piano roll turned sideways. Each box represents a note, like one hole on the roll of paper for the mechanical piano. The notes of the first voice are in blue; the second voice, when it comes in, is in green. The graphics below are themselves links that return larger images. The music icons play MIDI files.

As a first step in moving away from the familiar, the second voice begins at the same point, but the pitch is raised up a fifth.

Often times Nancarrow's canonic voices enter at different tempi. In the next variation, the second voice enters in the same place, but now plays at a faster tempo (in a ratio of 2:1 of that of the original voice) in order to end together with the first voice. This is referred to as convergence.

The tempo of the first voice is 120MM, the second voice when it comes in is 240MM in order to get through the same number of notes in half the time. In the frequency domain a 2:1 ratio in pitch results in the interval of an octave. This pitch interval is consonant, and the same ratio of tempi between two voices could be considered equally consonant in the temporal domain. Moving the starting point of the second voice back towards the beginning of the piece, while keeping the same goal of converging at the end, results in a slower tempo for the second voice. Depending on where the voice comes in the ratios of tempi will be dissonant to varying degrees.

In the next example the second voice enters where it would in the traditional version (but on a different pitch). There gves enough time for the first voice to establish its character so that the second voice can be recognized as imitation. The tempo ratio between the voices needs to be a 4:3 ratio if the two voices are going to converge at the end.

[ more examples of convergence ]

The opposite of convergence is divergence, where voices start together instead of end together, and then get out of synch due to their different tempi. In the next example both voices start together, but immediately begin to drift apart in a tempo ratio of 32:31. This is quite dissonant, and would take hundreds of beats before notes in the two voices would again sound simultaneously. It cannot be performed accurately by musicians without the assistance of some sort of special conducting system. Its realization is better suited to a player piano or computer.

A pitch interval of 32:31 is somewhere in the neighborhood of a quarter step.

Instead of beginning a diverging section with simultaneous entrances Nancarrow often begins with a rest (such as in the first canon of Study No. 37).

As mentioned in the paper, Nancarrow was more concerned with temporal dissonance than harmonic dissonance. A converging section, whose elements end together, can be thought of as temporally closed, while a section that diverges is temporally open, in the same way that sections of traditional classical music can be described as harmonically open or closed. Study No. 37 ends with a converging canon on a big C major seventh chord, making it both temporally and harmonically closed.

[ Study No. 37 ]