Robert Willey

University of Louisiana at Lafayette

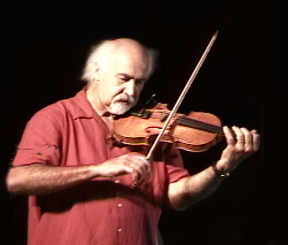

Michael Doucet has helped bring French music of Louisiana to a national audience with his recordings and performances with Acadian music groups and the band BeauSoleil. He is a Grammy award winner and was presented with an honorary doctorate in music from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. He appeared there as part of the Music Industry Lecture Series on September 25, 2002.

Please tell us about your background.

Everybody here wants to be a musician? Everybody wants to be rich and famous? OK, that’s what I’m here for—to dispel all your dreams. No, I’m just kidding.

I was born in Scott, Louisiana, which is right down the road. My parents were not musicians, but everyone else around was. I grew up in a rural area, my father just retired from the Air Force. I had all kinds of relatives that played. Some played classical music, some played piano, some played guitars, some played fiddles, some played trombones, so it was a cacophony when we got together because usually when we got together for parties everyone would make music. I wanted to play guitar really early, I think, that’s what everyone tells me. I was born in 1951 and Elvis made his big hit in ’56, so at five years old I started memorizing all Elvis Presley songs that I heard on the radio, so they told me. I don’t really remember this. I started performing when I was six. They gave me a banjo, which I totally destroyed. The next instrument was a trumpet. I had an uncle who played violin and fiddle in dance bands. He was a close uncle to me but was the kind of uncle that my parents didn’t want me to hang around with, because he also had a race track. Now it seems that musicians always hang around with crazy things. This racetrack was not a circular racetrack, it was the kind of quarter of a mile racetracks people used to have where gentlemen get together and bet and have a good time and play music. That’s basically what I remember about it.

From then I played trumpet and then guitar, played folk music, I went to L.S.U. This is a funny story, I hardly tell this one. I had three different scholarships when I went to school. One was in English, one was in track believe it or not—I threw the discus and ended up running the decathlon for two years and almost dying, and the third was in music. We’d do P.E. for half the year and then we’d do chorus. I’d sing bass, even though I can sing tenor, too. So we had this mixed quartet and we had to go around and sing and perform at state rallies. When I was a senior we were taking placement tests at L.S.U.—I don’t say this for you to do it—this is how not how to do this thing. Right next to L.S.U. there was a bar, the Target Bar, we’d already graduated from high school so it didn’t really matter, we did all our academic testing in the morning, so I said let’s just go get a beer, we were 18 years old. At that time you only needed to be 18. We drank a beer and suddenly somebody rushes in and says “You’re on right now, you have to perform!”. We ran over to this place at L.S.U., the room was like a pit and you’re right in the middle with the piano teacher on the piano who was growling at us. We did this mixed quartet song, you know, we were pretty loose. We had a good time. I went to a Catholic school. There was a nun there who was about to expel me, she said to go over and see what our score was. I came back and said we got an “S”—she couldn’t believe it, went running over to the board and was pushing people out of the way to see. We were the only group that year to make a “Superior”.

Music is what it is. You have to put your heart into it. At L.S.U. I took this course called “Anglo-Saxon Folk Music” that was given by Dr. George Foss. He and Robert Abrahms had written a book by the same name. I said “This is going to be nice.” I go to the first day of class and he says “We’re going to study mountain music, child ballads, blues, Native American music.” “What about French Music of Louisiana?” “Oh, no”, he said, “that’s just translated English songs.” That prompted me right away to do research on this music. I grew up with French music. People ask me how I learn to sing the songs. I say “How did you learn to sing your first Christmas songs?” You don’t remember those things. These things are so intertwined with our tradition.

I went to the L.S.U. archives and found this amazing plethora of information that I had not known. People like Harry Auster, he was an English teacher there at the time. He recorded people in Angola like Lead Belly and blues people, he recorded Cajuns and different Louisiana musicians in the ‘50’s. I found his field recordings—they were amazing. Also, I found a woman by the name of Irene Whitfield’s 1939 thesis called “Cajun Creole Folk Songs”. Unbeknownst to me this person was very much alive, so when I came back to Lafayette I asked my great aunt who was a school teacher if she knew this woman and she said “Oh, yeah, she lives over here” and there were good friends. She played violin, she gave me my first Amede Ardoin and Dennis McGee 78 r.p.m. record. Her cousin was Lauren Post who actually wrote “Cajun Sketches”.

I gave my report, which was all about this and George Foss and I became good friends, not because he taught me these things but because I knew there was something there that wasn’t being told. That was my mission, to tell the story about our culture and music. From that things just happened. I started playing up in France, taught school there. I was awarded a couple of grants here from the National Endowment for the Arts to go out and transcribe songs that hadn’t been done before because there was a barrier. I spoke French, they spoke French. Some people that I found hadn’t played for thirty years and had never recorded, they were just known by hearsay. These people not only gave me an incredible wealth about history—our own history, their own history, but about the music itself. I would transcribe a song that someone would call in Vermillion parish and go up to Evangeline parish and it would be basically the same song but they would say that they had written it. I went out and visited a lot of these people.

I was also interested in ballads, which was not a very popular thing. Not only were there not very many young people interested in playing Cajun and Zydeco music at that time, nobody was singing ballads because they took effort. Ballads were unaccompanied and people had maybe fifteen verses. To me that was really the basis of all our music. They were regular people, they weren’t performers or anything like that. If they would sing it would be among family members in their own household. I heard amazing work songs about kings and queens—I think the people who sang them didn’t know what they were talking about because there are no kings and queens here. I kept on doing that.

We were in France in 1976, playing on the Bateaux Mouche, this gentleman comes up to us and says “That’s very good music. Have you all recorded?” “No, no, man.” “Would you all like to record?” We said, “Yeah, sure.” He gives us his card, he’s the president of marketing at E.M.I. We said we were in Paris for only about five more days, he said “No problem”. He gets us this incredible studio, we go there and just play songs we’d learned. It wasn’t planned.

From that I got another grant to work in the schools with the late Dewey Balfa. It sounds like an easy thing but it really wasn’t. In those days in the mid ‘70’s Cajun music was just like our culture and language, it was really put down. People wanted to be American. You’d think after being here for two hundred years we would have learned, but we didn’t. People wanted to just dismiss this whole culture that we have. It was a battle going to schools. We had several principles refuse to let us in. This was something that was supported by the National Endowment. It didn’t cost the schools anything. There were four people. Usually there’d be a Creole musician, a ballad singer, an accordion player or fiddle player, whatever, and I’d tell the story, the history of this, what town it came from. This was throughout southwest Louisiana. They didn’t want that kind of music in their schools.

In 1980 we were awarded another grant, a Francophone Studies grant. I actually taught here [now U.L.L], devised a course called “Louisiana French Music: Opera to Zydeco”, which for me is one direct line. You can trace some of the songs from operatic verses in what you hear today.

And then, lah dee dah, boom--a fat guy from Opelousas, Paul Prudhomme burns a red fish, all of a sudden it becomes really popular, people start listening to the music. All this time we’re playing little folk festivals in French-speaking country and not really trying to make a living, never thinking we’d sing in the United States, because we sang in a different language. Then it happened—we were getting calls, we never really solicited. There were Cajun music festivals in Rhode Island, we played in Newport, Carnegie Hall in ’82, all these incredible gigs. People back home couldn’t believe it. I knew what I was doing, what I wanted to play, how I wanted to play it, at the same time learning our history and traditional songs was what I was interested in doing and showing people, and at the same time composing songs. That’s what we’ve been doing.

The original group that recorded split up, people split up and did other things. The group reformed a year later with my brother and a percussionist. I always thought that what makes Louisiana music different is the rhythm. The rhythm is different because of where we live, it’s the cadence. People say “Oh, Acadian music. You play Canadian music”? I say, “No, it’s not even close.” Our rhythm of life is different. Music is so earthy, it represents where you come from. That’s why it’s only made here, it’s only created here, by us.

What is your relationship with record companies like Rhino and Rounder Records? What are the opportunities for recording contracts and distribution for roots music?

We’ve been on every label. We’ve been on Swallow, Arhoolie, Island, Sony…Rhino was a great label. Rounder was founded back in the ‘70’s by three hippie-type people who liked good music, blue grass music. They’re good people but it’s a rough organization. They signed us, we were with them for a couple of years but weren’t very happy with it, there was no distribution. In those days, when we still had vinyl in the ‘70’s up to the mid-80’s, if you were from here and had an album or 45 that sold 2000 copies of a record, that was a big seller. This is a mistake I made. On the first record we had with Rounder in ’85. I put my phone address and telephone number on it. I figured I knew everyone who would buy it so it was no big deal. Well that record was nominated for a Grammy. I’d get all these calls, it wasn’t exactly what I wanted to do. I found that more people wanted to buy it and couldn’t find it, there was a problem with the distribution. The people at Rhino Records were music lovers. They’d have a these old records in Santa Monica that they’d sell out of the back of a car.

An A&R agent named Gary Stewart heard us, we were playing at the Meltzer Jazz Festival, I met him, we became good friends, he’d send me calendars. One year he gave me a CD, I said “I don’t have a CD player.” He said, “You will.” He was right for a lot of reasons. I called him up and said, “Look, Gary, I’m not very happy with the contract, people are not hearing our records, if we’re going to do them we’d just as soon get them out there, if people don’t buy them, that’s all right.” I told him what we needed to make a record. Ten minutes later he called me back, we had a deal. That was it for seven records. It’s been the best situation I’ve ever been in. Every record we’ve released through Rhino, because they love it, has either won a Grammy or been nominated for one. This is the group, that before we went in, had what they call the “Stairway to Heaven Awards”, which was to make fun of the Grammies because the Grammies are a lot of bullshit. I’m sorry but it is. I’m the first to admit that. All of a sudden we get nominated and they say “Oh, no, what are we going to do?” Now we’re legit. The company started changing. They’ve been so good. We had complete artistic control. I said, “Gary, do you have a producer?” He said, “Do you want a producer?” “Well, no, we don’t really need a producer.” “Just go do what you do. Give us the package and we’ll go put it out.” This is a match made in heaven. It was great, and it still is. A little merger has taken place with AOL Time Warner. BeauSoleil was celebrating our 25th anniversary. We had this album coming out recorded live at Wolf Trap, the first time we’d play out of Louisiana in the States. I thought it was a pretty good album. Right in the middle it fell into the gaps. No promotion. The people I used to deal with in this company, half of them moved to Burbank and got swallowed up. I saw the writing on the wall. I called Gary and said I supposed he wouldn’t want to pick up our option. He said that I could write eight new songs that probably no one would hear, or they could do a “Best Of” album of things that had already been recorded to fulfill the contract. It doesn’t take an Einstein to figure that one out, so that’s what we did.

How is the music industry changing?

With the technology like Pro Tools that’s out there now you can record your own album. If you’re pretty, if you win the ridiculous “best of” thing on TV, then great, you can get a big deal, but other than that I don’t think it’s possible anymore. You can record and have control of your own record, 2-5 songs, it doesn’t really matter, put it up on the Internet, let people make copies of it, the deal is to play. I think that’s what’s coming down now. I think that because of Napster and Song List (you can get free songs), I think there is more of a demand for live music. I think that’s good, that’s how music is made. We’ve gone through all these things, you can go into the MIDI lab and make everything perfect and beautiful, but there’s something about being in a live performance that is just totally amazing. That’s what people want to go for. We’re sealing ourselves up so much with this prefab music that’s good, but you want to see soul, you want to see an individual’s spirit, you want to see what makes it, that’s what moves people.

Distribution on a national level has become so consolidated. It’s not as easy as it used to be. There are about five big companies that control it.

Can you give examples of what happens when you don’t have artistic freedom?

You get these idiot producers who want your sound to be a certain way, like give your song a Nashville sound. It would be a different arrangement, different mix, it wouldn’t have our kind of feel. They want to use our music as a little seasoning, like salt instead of Tony Sachets. Complete artistic freedom is what you want the song to sound like. A producer might have a better idea, I’m not saying that it’s all wrong. We just never had that. They never told us “We want a hit. Write a song in English”, although they were very happy when we did. We could do what we wanted. In some way we might have had a better career had we picked a genre that people wanted to hear. I hear that people who play elevator music get paid the most.

In Pollstar you can find distribution companies. BMI and ASCAP are the artists’ friends. You can distribute it through Amazon.com or locally through New Orleans. They take a percentage. All they do is distribution. 300-400 records come out a week, it’s ridiculous. You have to work with a publicist, they get the product talked about. It’s a cycle. It you do your own half of it goes to promotion. Send out copies to all the magazines to try to get it reviewed. You want people to know about it. Start with local papers and everywhere you play. Alternative newspapers and radio. Give it to all the disc jockeys. It’s work.

What is your relationship with booking agents and managers?

When I put my name on that record I became the booking agent. People came up to us and wanted to do this and usually they make 10-15% of what you make. They do good, you have to do it, they get you the gigs. You have to go with the agents if you want to play broadly. People were calling us up after ’85, I knew we needed an agency. We just had a friend who was doing the booking. In 1986 we decided to do this full time. I figured we needed an agent to do this if we were going to survive. It was the last year I taught here was ’86. Since we played folk music I thought we’d go with agents that do folk music. We’d played at a lot of places and met a lot of agents. Some had gold chains, some were just funky people, some were nice women who you’d never expect were on the phone trying to get you a job. So I went around and talked to a lot of people. A lot of them said that they were interested but nobody knew how to handle it, nobody had handled a Cajun band before, that played shows, dances, concerts, it was peculiar. One guy, John Elman, said that the first thing you have to do is tuck your shirt in. We had to play all these showcases which took some of the members of our group a while to do, and we had to stop wearing dirty blue jeans. We said, well this isn’t really us. He said if we wanted to go above and start playing these concerts this is what they expect. So we do this, we start to tuck our shirts in and boom--the gigs started coming in, they were pretty good. We still kept playing bars at that time.

This other guy named Hershel Freeman didn’t want any kind contract, he said we just shake hands and as long as we like each other we work together. I said that’s how we do things in Louisiana, that’s fine.

So we worked with Hershel for a while. He did everything himself, he didn’t have a secretary, we’d have little tours and go around. He kind of dropped the bomb when he found someone he liked better or was a little showier. We had become friends with a band called Los Lobos and they were with this agency called Rosebud in San Francisco. I looked at their roster and they had Bonnie Raitt at one time, and the Neville Brothers, J. J. Kale, John Hammond, I say “These are the people I really listen to, so I’ll just call them up,” and I did, and it’s been great ever since. I can’t say more about an agency than Rosebud. They have a great website, they’re very personable people. Again, a handshake.

Do you need a manager?

I think it’s a waste of time. I’d like to be a manager now so I wouldn’t have to go on the road so much. You might have a manager who’s a lawyer or who knows the business, or has a club or a series of clubs, that can help you out. If you believe in him or her, if they do something for you that changes your life. If they’re the kind of person who can look at you as a mirror and see what needs to be done and keep you on track if you want to make this a career, if you’re very serious about this. Obviously we’re unmanageable, so we never had a manager.

Why do you also play with Fiddlers Four?

Fiddlers Four is a great group, it’s a different extension for me, it’s a string quartet. The reason why they are with Rosebud is because of my crazy schedule. We play lots, and if I do something with someone else we have to coordinate it. It’s diversity. You don’t want to play the same kind of music all the time. I could do that and go to sleep, but I prefer to keep on learning and keep playing and have a good time.

What are the other kinds of things you’ve done besides being a songwriter and performer?

I got a call from Frito Lay to do a commercial about a new product called “Crunch Taters”. In ’85 I was still a protector of our culture, which was a ridiculous idea, I said as long as the word “Cajun” is not used. They said OK. I had to write a thirty second jingle. They came and filmed it. Then they wanted to show us, so we played at a club in Houston called the Hey Hey Club (??). It was part of a Showtime program, Chick Corea was the host, it was great meeting him. That’s when I learned about publishing and writing. The money was pretty amazing just for a thirty second spot. You get money every time it is aired. I said, “Well this is interesting.” One of the women asked if I belonged to SAG (the Screen Actors Guild). I said no. I was in a little movie with Glen Pete called Bellies of the Cajun I did the soundtrack to that movie with Howard Shure. She asked if I was a complete member, I said no I was an adjunct member, I didn’t want to join. She said “Join.” I said the dues are like a $1000. She said “Join”. So I did. Not only do you get ridiculous amount of money every time that is aired, I got free family insurance for three years from Blue Cross with no deductible.

I got a call from a lawyer from New Orleans, he said “They’re doing tryouts for a Maalox commercial. They want Louisiana music.” I asked him, “Ellis, am I the first person you called?” Well, no. I said, “I’m not the last person you’re going to call?” He said no. I said “I’m really not interested, I never win the lottery.” We were getting ready to go on the Conan O’Brian show, it was right before the Olympics, I guess that was three or four years ago now. I got a call from our record producer, Chris Strachwitz from Arhoolie Records, which is a roots label. He loves music, rediscovered Lightning Hopkins, put out the first Clifton [Chenier], he does Nartenien , Mexican, ethnic stuff, he hates commercial music, what he calls “Mouse Music”. He starts telling me about this commercial that I’d already heard about. He said that they wanted to use one of our songs. I thought they’d want to use it in some stupid way. No, he said, he thought it’s going to be good. This was on Wednesday. The spot aired on Saturday. They took the master off the CD.

Other forms of diversification?

I’ve done instructional videos with Homespun Videos, which is good. My wife and I, Sharon, and daughter, Melissa, and even Mathew was on that one, a little record for children called “Le Hoogie Boogie”. People still use the French version around here.

Memberships in any folkloric associations?

I don’t belong to any club that would want me for a member.

Scoring?

It was fun working with Howard Shure. The last thing he did was the soundtrack for Lord of the Rings. He used to be the band director on the original Saturday Night Live. He’s a very amenable guy, he knows music, he’s done a lot of scoring, he and I worked on “Bellies”. That was a lot of fun.

How can the university can help promote regional music?

They can hire me again! [laughs] The course I taught here was “Opera to Zydeco”. I think it should be something like “French Music of Louisiana” so that it incorporates everything. Our indigenous music here is Native American and French. You have a lot of different tribes and reservations west of here that still play music. This guy by the name of Leo Langley played fiddle and sang both in French and his Indian dialect. I think it’s important to see where we come from and to put it all together and showcase that, and perpetuate it. It shouldn’t be the same thing over and over. It should gain momentum and be creative and evolve. It could be a focal point if it were taken seriously.

Any suggestions for research topics?

The whole idea of folk music of the people, how do you learn a song? If I play a song for you and then you play it for the next guy it will probably change. How do these songs happen? It still happens nowadays. You listen to Bruce Springsteen and interpret it your own way. The whole creative process, that’s what I’m interested in. I think that’s the way to perpetuate this music or any music, whether it’s jazz or ethnic music. You’ve got all these groups that have improvisational music, what we call “jazz”—Klezmer music is the first thing that comes to mind, New Orleans jazz—which is not Dixieland, having that facility, to see what areas of the country and the world that become fused together.

What’s the outlook for Cajun music around the country?

We were kind of trailblazers. We played in all 50 states. North Dakota was the last one, and the weirdest, just wanted to let you know. It’s been pretty amazing. I never foresaw this, we can go all around the world, for some reason, it touches people. You play from your heart, you play good, people are there, they’ll come away different. Once we were playing in Petaluma, California—there was this girl who was moved. She’d never heard the word “Cajun” or “Zydeco”, I don’t think she knew where Louisiana was. She said “I know this music.” She ended up moving to New Orleans, I think she even plays music. We were playing in Connecticut, this gentleman says “I didn’t understand a word you said, but I don’t understand Italian either and I love opera.” There are going to be changes. We represented a different climate. We were resurrecting a dying climate. We put a lot of energy and pizzazz into it. We respected the past, at the same time brought it forward. There are going to be other younger groups that will have a different idea that can do their own thing. It has a niche now. Some of the record stores have a Louisiana section and I think it should be placed in there. For many years we were placed in “Folk” or “Blues”, they just didn’t know. Now people know what Louisiana music is. I think that Louisiana is the best place in the world for music. You have freedom here, you can play live music, people like to dance and go out, rather than be stuck in a place where you can’t perform.

Do you have any advice for students starting out in this field?

50% of this is hard work, getting your chops together, being talented and working with that talent, and having it inside, getting some sort of universal theme that doesn’t exclude anybody. The other 50% is playing as much as you can. The majority of what happens is being at the right place at the right time. Some people are already there. If you marry the right person, or your father is a famous somebody, that’s a way in the door. But things happen, things happen in strange ways. Always keep that in mind.

Good luck to you. Never stop. That’s the key. Never stop looking for opportunities. Never ever quit treating people like people. That’s where longevity in the music business and life is.

[ Interview part 2 ]

Bibliography

Roger 0. Abrahams and George Foss, Anglo-American Folk Song Style (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1968),